Executive Functions: Focused Interventions for Planning and Prioritizing Deficits

Planning and prioritizing are essential life skills because they help a person identify and focus on not only what needs to be accomplished, but the order in which the tasks should be done. Being able to construct a plan and then prioritize the necessary events and steps is an essential 21st century skill, in that it is necessary for balancing and maintaining a relatively sane life.

Although related, planning and prioritizing are not the same, but they are two sides of the same coin. In fact, the two are so interconnected that plans would immediately turn to ruin if they were not able to be effectively prioritized. For educational purposes, planning and prioritizing are defined as follows (Remoreras, 2011).

- Planning is thinking about the tasks required to achieve a desired goal. As students mature, they are gradually expected to exercise greater control over their ability to plan. However, to do so, the art of planning must be modeled and practiced over the course of time so that students can be successful on their own.

- Prioritization ensures that you are doing the right tasks, and in the correct order. Dawson and Guare (2009) define prioritization as, “The ability to create a roadmap to reach a goal or to complete a task. It also involves being able to make decisions about what’s important to focus on and what’s not important” (pg. 8).

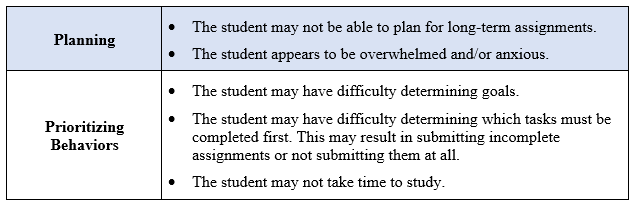

The following behaviors are common in students with executive function deficits in planning and prioritizing (Strosnider & Saxton Sharpe, 2019).

Proximal Goals: The Path to Better Executive Skills

Research has shown that proximal goals, or ones that are attainable in a fairly short amount of time, provide more immediate incentives for students who have executive skill deficits. For example, a proximal goal such as, “I will read one chapter of The Great Gatsby tonight” has been found to be much more effective in stimulating students’ planning and prioritization skills than a more long-term distal goal such as, “I need to finish reading The Great Gatsby by the end of the month.” (Schunk, 1980; Meltzer, 2010). The reason for this is that because in addition to being more detailed and specific, proximal goals are also more personal and attainable, given the shorter timeframe.

There are many benefits of setting specific proximal goals for students. First, goal setting increases student motivation. When students have a specific, short-term goal to attend to, motivation is increased, as they now have a specific focus for which they are working. Second, setting goals increases achievement. Since goals should be directly tied to data, targeting a specific deficit boosts knowledge and achievement. Finally, students start to feel of sense of accomplishment as goals are conquered, one by one. Oftentimes, students tend to view a daily difficult task as impossible, or insurmountable. For example, when thinking about running a marathon, how overwhelming does twenty-six miles seem? However, if you start by running just one mile, then two, then three, etc., before you know it, the twenty-six miles seem to fly by! By establishing small, manageable goals, students can chip away at that once-impossible task which stimulates their executive skills so that they can feel a sense of accomplishment and pride.

Writing Goals that are S.M.A.R.T.

Writing effective goals is a process and therefore, it will take some time for students to master both writing and achieving their goals. The following are some suggestions of things to consider before starting goal writing with your students.

- Look at the data. Data patterns need to be discussed. For example, if you are teaching how to divide fractions by fractions (6.NS.A.1) but a student does not even know all his/her basic division facts, s/he should be made aware of his/her goal. Then, the teacher and the student can work together to set smaller, proximal goals so that the ultimate mastery of the standard can be achieved. Teachers should be sure to seek out areas in which individual students feel they struggle. This part of the process is critical, as students need this data to create meaningful proximal goals for themselves.

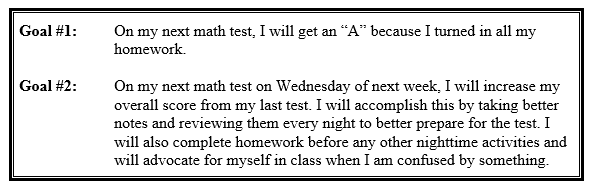

- Guide students in setting goals. It can be difficult for teachers to let students take the lead when setting goals, as most teachers have their own goals in mind for their students. However, it is crucial for students to determine their personal goals on their own, even though it is perfectly acceptable to prompt and/or guide them along the way. Encourage students to select only one or two goals at a time so that the task itself does not become an overwhelming process. Finally, make sure that students are thinking S.M.A.R.T. when choosing their goals. The S.M.A.R.T. acronym, as shown below, is a great guide for helping students write Specific, Measurable, Actionable, Realistic, and Timely goals. Look at the difference in the following two goals. Which one is a SMART goal?

The second goal is a S.M.A.R.T. goal, as it is specific (increasing the overall math grade from a prior test), measurable (e.g., a math test score), actionable (e.g., taking better notes, reviewing notes, and completing homework), realistic (it is more than possible to increase one’s grade from one test to the next, provided the student puts forth the required effort), and has a timeframe (e.g., on Wednesday of the next week). The first goal is too vague and does not incorporate all the S.M.A.R.T. elements. When writing S.M.A.R.T. goals, it will take time and trial and error, but eventually students are bound to grasp the concept and the resulting benefits.

S.M.A.R.T. Goal Action Plan

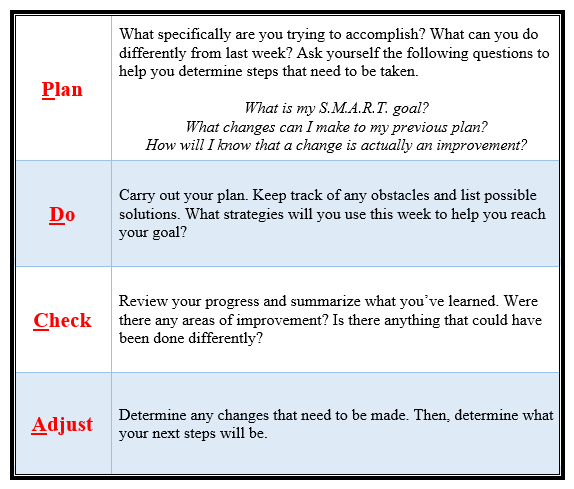

What if students are struggling to meet their goals? It can be easy for students to give up and abandon their goals when they feel like they’re struggling to achieve them. For students who have executive function deficits or are simply having a harder time meeting their goals, assist them in reevaluating their goals by examining the progress they’ve made and identifying any roadblocks that may have come up (or will come up in the future) by teaching them a strategy known as the PDCA Cycle. This is also referred to as the Deming Wheel or Deming Cycle because it was made famous by the statistician, Dr. William Edwards Deming.

To help students stay consistent in meeting their S.M.A.R.T. goals, they can develop an action plan to track their progress. Having a plan laid out ultimately helps students as they try to visualize just how they will achieve their goals.

Planning with First-Then Schedules

Learning how to effectively plan and prioritize can be a very difficult task to master, as it encompasses a variety of other executive functions as well. Not only do students need to know how to plan and choose the most important items in order of urgency, but this skill requires them to also be able to initiate the task, organize any necessary materials, shift between tasks, and limit their impulses, all while self-monitoring their progress. So, it is not surprising to discover that students with executive function challenges often have trouble with planning.

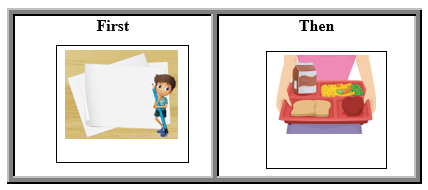

A first-then schedule can be created to help students with this executive function deficit see that first students will be working on writing; then they will go to lunch. A first-then schedule can easily be created using pictures that attach with a hook-and-loop fastener. This allows each set of pictures to be easily changed from one activity to the next. First-then schedules teach students the importance of prioritizing tasks.

Planning with Project Mapping

As students get older, they are expected to be able to plan and prioritize more lengthy and complex projects. Not surprisingly, students with executive function deficits can find this task to be extremely difficult because long-term, distal projects by their very nature require heavy planning and prioritizing. In cases such as this, it is helpful to break the long-term project into smaller, more manageable chunks. Typically, because they do not understand the discrete parts that make up the long-term project, they underestimate the amount of time that is needed to complete the project.

To combat this, many teachers have turned to a strategy known as project mapping. Project mapping allows students to visualize the discrete parts of the project/assignment and as they break it up, students put a time frame on each of the parts. This causes them to engage their planning and estimation skills, as students must have a rough estimate of the amount of time the project will take to complete. As they work on completing it, students monitor their progress.

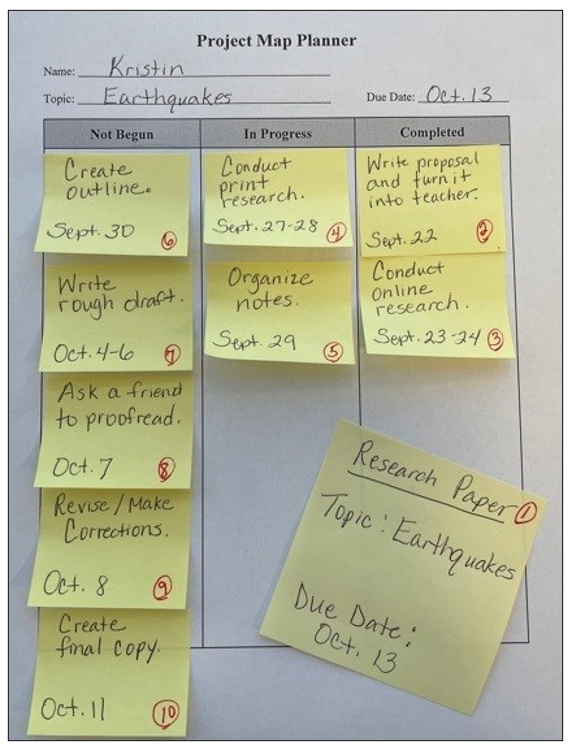

To begin mapping out a long-term project, use a project map planner, like the one shown below. It is divided into three discrete parts.

- Not Begun

- In Progress

- Completed

- Have students identify what their finished product will look like. Will it be a written report? An oral presentation? Some type of model? Using 3 x 3 sticky notes, ask students to write down the basic information regarding the project, including the designated or pre-determined format and topic. At the bottom of the sticky note, have students record the due date of the project.

- Brainstorm all the different tasks that need to be completed to finish the project. Write each part on a separate sticky note.

- For each task, estimate the amount of time it will take to complete (e.g., two days). Use a calendar to assign dates to each task, making sure to give each task the appropriate amount of time that was originally estimated. This helps ensure that all the tasks will be completed by the final due date. Write the due date for each task on the bottom of each sticky note.

- Place the sticky notes in order, using the project map planner. At first, all tasks should be in the “Not Begun” column.

- As tasks are begun and make their way through the planner, move each sticky note accordingly.

Another Essential Executive Skill

When juggling all the responsibilities that school brings, learning to set goals, plan, and prioritize can help students manage their workload without becoming overburdened and overwhelmed. These essential executive skills are invaluable to master and as with many executive functions, it can be difficult for some students to do so. By using the strategies outlined in this article, students can eventually learn how to juggle these various skills so that they can organize their workload to create a realistic plan of action that can be managed efficiently and effectively.

Are you curious? Want to take a deep dive on this topic?

To learn more about the impact of executive function skills and how to use focused interventions to support students in developing their executive function skills, visit the Professional Development Institute (PDI) website or go directly to our Focused Interventions to Improve Executive Function Skills course.

For over 27 years, PDI has provided high-quality and affordable online professional development courses to K-12 teachers worldwide. Our online courses are designed to offer practical strategies that can be implemented in classrooms immediately. All our courses are instructor-led and conducted entirely online. Graduate-level university credit for every PDI online course for teachers is available through the University of California San Diego Division of Extended Studies. PDI offers an extensive catalog of online courses that cover the most critical topics in today's classrooms.

References:

Dawson, P. & Guare, R. (2009). Smart but Scattered: The Revolutionary “Executive Skills” Approach to Helping Kids Reach Their Potential. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Meltzer, L. (2010). Promoting Executive Function in the Classroom. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Remoreras, G. (2011). “What Prioritization and Planning Can Do for You.” [Blog Post]. Retrieved 09 Aug. 2021 from https://glennremoreras.com/2011/01/12/prioritization/

Schunk, D. H. (1980, September). Proximal-goal facilitation of children’s achievement and interest. Paper presented at the 88th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Montréal.

Strosnider, R. & Saxton Sharpe, V. (2019). The Executive Function Guidebook: Strategies to Help All Students Achieve Success. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Categories: executive function skills, teaching strategies

View PDI's Catalog of Courses

Check out a list of all PDI graduate-level online courses or sort by grade level or subject area.

Register Now!

Quick access to register for PDI's online courses using our secure system.

Learn More about PDI

Find out how to reach PDI and get answers to any questions you may have.

Access My Course

Access PDI's online learning management system to begin your course.