Executive Functions: Focused Interventions for Self-Monitoring Deficits

Self-monitoring is related to the metacognitive strand of executive function skills. When students use metacognition, they think about their thinking as they read, write, perform calculations, and socially interact with their friends and classmates. Having the ability to think about their thinking allows students to self-monitor their behaviors and actions, so that they can respond appropriately as they confront the inevitable changes and obstacles in their path to learning. Self-monitoring is a critical executive function because it teaches students to self-assess their behavior and record the results.

The Elements of Self-Monitoring

Self-monitoring is but one of the components involved in self-regulation. To complete learning tasks, students must use this executive function to ensure that they are on the correct path to successful completion. This requires them to not only know and understand a variety of metacognitive strategies, but they also must have the ability to sense which ones to choose, when and how to use them, and be able to assess their effectiveness. If all is well, great! But if not, self-monitoring also allows students to adjust their approach. Students who are adept at this executive function constantly ask themselves questions, such as the following (Wilson & Conyers, 2016).

- How well do I understand this lesson or situation?

- How can I evaluate my understanding, and what more do I need to learn or do?

- Which cognitive assets can help improve my learning so that I can reach my goal?

The ability to track one’s progress throughout the learning cycle is what is known as self-monitoring. This is especially relevant to education because many state standards require students to use and master this executive function. For example, most states’ reading standards require students to self-monitor their comprehension as they read and clarify their word usage as they write.

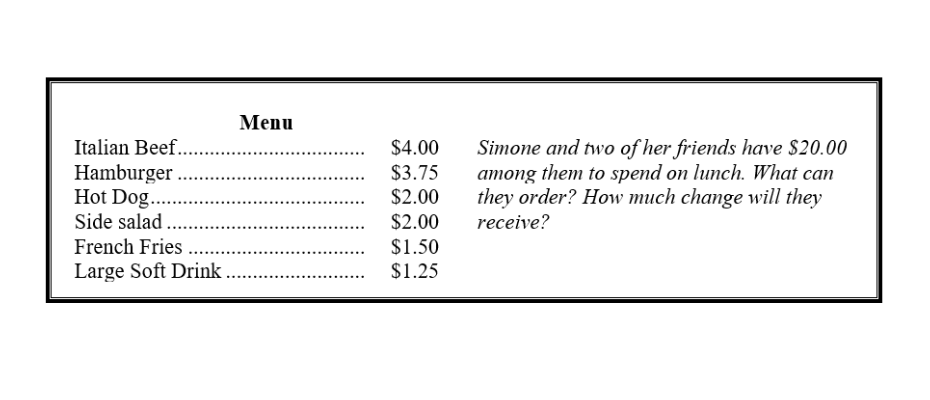

One of the key elements involved in self-monitoring is cognitive flexibility, or “the capacity to objectively consider two or more concepts simultaneously and to recognize when it may be useful to adjust one’s thinking and actions based on new information” (Wilson & Conyers, 2016, p. 90). In other words, students must possess the necessary skills to adapt their thinking and behavior in response to their environment. Thus, when a student is confronted with an open-ended real-world problem that requires him/her to think about multiple concepts simultaneously, s/he must engage in flexible thinking to solve the problem. The example below has no single “correct” answer and as a result, students must use multiple metacognitive problem-solving strategies to arrive at a logical and “correct” solution.

This executive function uses two skills — flexible thinking and set shifting. Flexible thinking occurs when one can think about something in a new way. Set shifting happens when one is able to let go of the “old” way of doing something in order to tackle it in a new way.

A second element involved in self-monitoring consists of the ability to evaluate one’s own effectiveness. Students self-monitor themselves all the time. As they read, they ask themselves if what they are reading makes sense. If it does, great, they forge ahead; if not, they employ a variety of fix-it strategies to improve their comprehension. In math, if an answer doesn’t make sense, they go back into the problem and try a different approach. And this important executive function is not just relegated to academics. Students use self-monitoring strategies as they navigate the complex relationships around them. They use them to understand directions, keep track of due dates, check their work, and interact with their teachers and peers.

Focused Interventions for the Classroom

One of the many advantages of self-monitoring is that it is relatively simple to implement in the classroom. Studies have shown self-monitoring strategies to be highly effective for students in a wide variety of settings and different content areas (Cook, 2014). Self-monitoring can also be used in combination with other metacognitive strategies, such as goal setting or independent learning. When all is said and done, self-monitoring is a best practice to support the academic and behavioral performance of students.

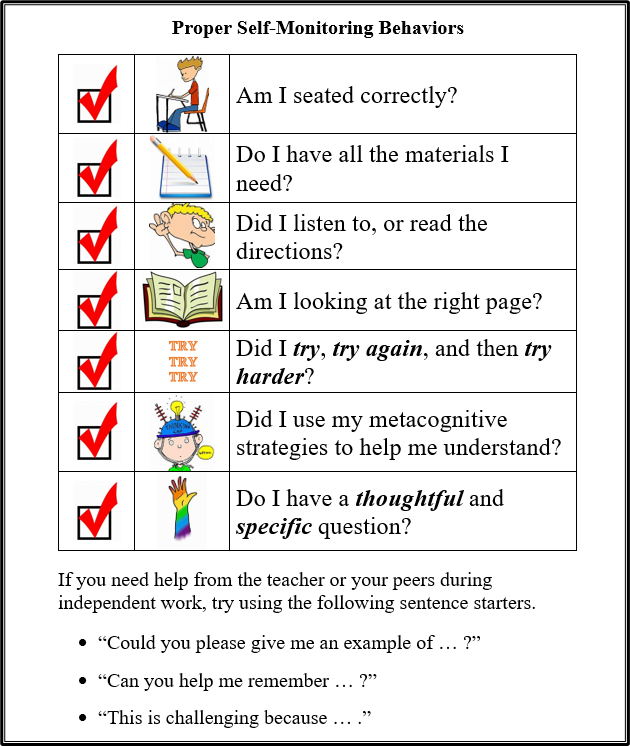

The following anchor chart is designed to help students remember the behaviors that are typically associated with self-monitoring. This document can also be printed and used individually with students as a checklist.

In terms of work-checking behaviors, the following interventions can be used with students who show weak self-monitoring skills.

- Establish a set review and edit procedure. Teachers need to build a review and edit procedure into their daily classroom routines. Doing so ensures that students are trained to self-monitor their work-checking behaviors so that tasks are more readily and easily completed. This involves setting aside time to attend to this aspect of task completion. A task completion checklist can be created ahead of time. Students should be explicitly taught how to use it and they should have ample practice with it before moving the expectation to independent use.

- Focus on accuracy rather than speed. The goal-setting process for task completion should focus on accuracy, as opposed to the speed of work completion. Because students with executive function deficits often cannot complete a skill quickly, they tend to focus on simply getting it finished. When compelled to act quickly, speed becomes emphasized over accuracy and in the process, students lose sight of the goal, causing them to miss the point of the task entirely. To help in this regard, consider differentiating the task by process or product, so that the same content is still being learned; the only difference is that accuracy is now favored over speed.

- Specifically teach time management skills. Students who have weakened self-monitoring abilities often demonstrate a poor awareness of time. Draw students’ attention to the correlation between productivity and time. To make them more aware of this correlation, consider implementing a series of predictions related to how much work they expect to accomplish within a given period. Allow them to work for that period and then assess the accuracy of their prediction.

- Encourage students to use external cues. The use of external cues such as a clock, timer, or the progress of their peers helps students assess whether they need to adjust their speed so that the task can be completed on time.

There is no “I” in Team!

Purposefully monitoring one’s learning is at the heart of metacognition. Students cannot successfully complete a task until they first learn how to self-monitor their thoughts and actions. In doing so, students can successfully plan, initiate, organize, prioritize, and shift, all while metacognitively keeping all the moving parts in working memory. As this begins to take shape, teachers guide their students using the gradual release of responsibility model so that eventually these self-monitoring strategies become second nature.

Are you curious? Want to take a deep dive on this topic?

To learn more about the impact of executive function skills and how to use focused interventions to support students in developing their executive function skills, visit the Professional Development Institute (PDI) website or go directly to our Focused Interventions to Improve Executive Function Skills course.

For over 27 years, PDI has provided high-quality and affordable online professional development courses to K-12 teachers worldwide. Our online courses are designed to offer practical strategies that can be implemented in classrooms immediately. All our courses are instructor-led and conducted entirely online. Graduate-level university credit for every PDI online course for teachers is available through the University of California San Diego Division of Extended Studies. PDI offers an extensive catalog of online courses that cover the most critical topics in today's classrooms.

Categories: executive function skills, teaching strategies

References

Cook, K. B. (2014). “Self-Monitoring Strategies for Improving Classroom Engagement of Secondary Students.” Georgia Association for Positive Behavior Support Conference, Atlanta, GA, December 2014

Wilson, D. & Conyers. M. (2014). “Cultivating Practical Optimism: A Key to Getting the Best from Your Brain.” Retrieved 16 Aug. 2021 from https://www.edutopia.org/blog/cultivating-practical-optimism-donna-wilson

View PDI's Catalog of Courses

Check out a list of all PDI graduate-level online courses or sort by grade level or subject area.

Register Now!

Quick access to register for PDI's online courses using our secure system.

Learn More about PDI

Find out how to reach PDI and get answers to any questions you may have.

Access My Course

Access PDI's online learning management system to begin your course.