Discovering Your Own Growth Mindset

In today’s modern society, we find ourselves in constant communication with one another via messaging apps or social media platforms. Perhaps no other time in history would bear witness to people so consumed with their sense of self. Dissatisfied with a product? Tweet out your disappointment to the universe. Indulging in a meal at your favorite burger joint? Slap a picture of your plate on Instagram. Having a good hair day? Upload a snap of those awesome tresses to your Snapchat story. Selfies, anyone? The list goes on and on.

As a result, many of us either knowingly or unknowingly expend a great deal of energy seeking out or labeling probable causes, which keeps us from reaching our goals. Thanks to social media, we are inherently aware of how we stack up compared to those around us. We repeat variations of statements like the ones below to validate the persistence of our predicaments.

- “I've always subscribed to this particular school of thought, so there’s no sense in changing now.”

- “I'm not good enough to ________.”

- “This is the way I was raised, so I am not going to question it.”

- “Why put forth so much energy and effort? It will never happen to/for me/you anyway.”

- “It’s too much work.”

- “I’m too old/out of shape/poor/etc.”

Perhaps you have even pronounced a few of these limiting phrases to yourself or to others while embroiled in debate or conversation. And yet, the question remains: why do we continue to champion for our limitations? The research confirms that our intelligence is not fixed, as we once believed it to be. Given the recent foray into studying the brain’s response to a variety of stimuli or tasks, we now know that the brain can readjust itself and evolve. If the hard science exists outside of it, surely the readjustment of our inner voice can subsist within us (Lynch, 2018). As the old adage goes, you can’t pour from an empty cup. In the same way, teachers who possess a fixed mindset of their own are not equipped with the tools or framework for “instilling a growth mindset” in those they influence and teach.

As teachers, we would be remiss if we did not consider the impact that our own assumptions and mindset has when it spills over into the classroom. Perhaps there are those among us who recall the “self-esteem” movement, and it’s likely there are those of us who may have been the target audience when we were in school. We know our students leave our classrooms and take part in a myriad of activities where they may receive a very mixed message on mindset. Perhaps early on, children become accustomed to the practice where every player on a team receives a medal for participation alone. This somewhat controversial practice can swing the pendulum in one of two ways. Some children may believe that ultimately, their effort and improvement was recognized even if s/he did not walk onto the field, immediately possessing the ability to play the game with ease. Other children may take this participation medal as a sign that it does not matter how well one tries or how much effort one exerts. In their eyes, everyone gets the same result and receives the same accolade, therefore nullifying a sense of competitiveness. Yet, as students age, they often find themselves the recipients of a fixed mindset way of doing things, when one is “cut” or fails to earn a spot in the school musical or the basketball team on the basis of their inherent skills or abilities.

We occupy a world which is mesmerized by the idea of “genius” and “giftedness” and how early it can be discovered or assessed. Videos go viral across social media platforms of child prodigies who are able to play Tchaikovsky by ear or teens who can play through all the levels on a popular video game while blindfolded. Every four years, we sit glued to our televisions watching the Olympic games, reveling in the belief that a particular phenom was “destined” to play or compete in a particular sport. The media hypes up the idea of a predetermined or inborn talent without acknowledging how these stories often dismiss hard work and grit. As the groan-worthy joke goes, “How do you get to Carnegie Hall? Practice, practice, practice!"

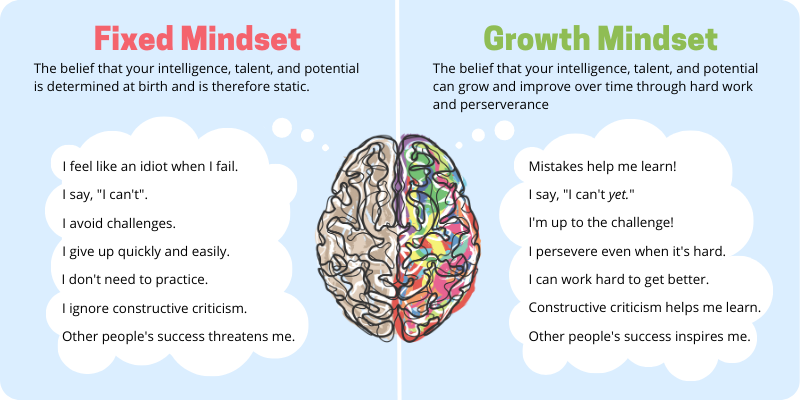

Consider the table below (Bolton, 2015) and note the differences in statements uttered or associated by those in possession of a particular mindset. Do you find yourself aligning with any of the statements made?

Do You Have a Fixed Mindset or a Growth Mindset?

| Common Statements or Beliefs Associated with a Growth Mindset | Common Statements or Beliefs Associated with a Fixed Mindset |

|---|---|

| My intelligence (no matter my age or educational background) can be continuously developed. | My intelligence is static and is pre-determined by factors beyond my control (e.g., genetics, educational opportunities, socioeconomic factors, etc.). |

| I embrace challenges that come my way. | I avoid or deflect challenges whenever possible. |

| I persist through obstacles. | When I encounter an obstacle, I prefer to give up and move on to a task which is better suited to my interests or talents. |

| If I falter or fall short in accomplishing a goal, I try again. | If I falter or fall short in accomplishing a goal, it is easy to conclude that it was not something I was capable of accomplishing in the first place. |

| The more effort I exert, the bigger the payoff. | Despite how hard I work, I do not make noticeable improvement. My skill level remains the same or in some cases, worsens. |

| I can receive and learn from the feedback or critiques I receive from others. | Feedback or constructive criticism is very disheartening to me. |

| I can learn from others who have found success in related endeavors and draw inspiration from their work or words. | I feel uncomfortable and even threatened by the success of others. |

Growth vs. Fixed Mindset

Let’s recall that the most prominent line between the two mindsets is the belief in the permanence of intelligence and ability. One views it as a constant, with little-to-no room for change in either direction. Meanwhile, the other mindset is characterized as being more prone to change, with opportunities for improvement. These differences may result in noticeable differences in behavior as well. If someone believes intelligence and abilities are static traits, it is unlikely that s/he will be willing to put forth much effort to attempt to change his/her level of intelligence or ability. Alternately, those who believe they are in control and have the power to change said traits will possess the grit needed to put in extra time and effort in the pursuit of more ambitious goals or endeavors. Those in possession of a growth mindset are more likely to use their time productively as opposed to worrying constantly about being the best or illuminating their talents to those around them. This provides them with the freedom to think creatively and place a more concentrated effort upon building up their intelligence and interests (Dweck, 2015).

While the benefits of instilling a growth mindset in students are tenfold, Dweck does not hesitate to point out that it’s not just about telling yourself (or others) that you “can improve.” Having a growth mindset is not about being open-minded or being a flexible thinker. It is more precise than this. It is not just about praising and rewarding effort, as that is not necessarily tied to measurable outcomes. Being passionate about establishing a flexible mindset or cultivating one in the students you serve may lead to positive outcomes; but it is not a guarantee. The mindset must be supported by carefully curated activities and even then, student success or personal success is not a foregone conclusion. Rather, a growth mindset is a way of thinking which is something that all teachers should strive to give their students. When we live with a growth mindset, we see possibilities instead of limitations. Our failures become valuable experiences for learning. Success attained by others should inspire us rather than provoke a feeling of self-doubt or jealousy. Most of all, we should view our efforts as important steps on the pathway to a meaningful journey rather than as a bridge to nowhere. This is the kind of self-awareness we must foster in ourselves in order to be equipped to prepare our students to succeed in exciting ventures, which will stretch far beyond the bounds and limitations of the traditional school model (Dweck, 2015).

Consider what damage can be done when teachers or parents claim to embrace or implement a growth mindset in themselves or their homes, but lack the tools to follow through. In recent findings, Dweck herself found that there were many teachers who endorsed a growth mindset and even said the words “growth mindset” continuously within their classrooms, but failed to follow through with meaningful classroom practices. As a result, the students in these courses tended to endorse more of a fixed mindset about their abilities. Longtime Dweck collaborator, Kyla Haimovitz (2016), finds that many parents are quick to endorse a growth mindset but react to their children’s mistakes as if these errors are a harmful byproduct, instead of a helpful mistake. In these instances, the only mindset — which flourishes and is fostered — is highly characteristic of a fixed one.

One of the best things that you can do is to take an honest assessment of your own mindset. Realistically, is it more characteristic of a fixed or growth mindset? Perhaps you’re the person who was referenced earlier who fluctuates on the mindset continuum, depending upon the given situation. Keeping an open mind, take some time to complete the mindset quiz below and see if your results align with your own self-assessment.

Mind Your Mindset

Circle the score in the column that best identifies the extent to which you agree or disagree with each statement (Bolton, 2015).

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Your level of intelligence is something you’re unable to change. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2. | No matter how much intelligence you are born with, you have the power to change it. | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 3. | You can always change how intelligent you are. | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 4. | You are a certain kind of person, and there is not much that can be done to really change that. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 5. | You can always change basic things about the kind of person you are. | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 6. | Musical talent can be achieved by anyone. | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 7. | Only a small number of people are truly good at sports — you have to be “born” with certain skill sets. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 8. | Math is much easier to learn if you originate from a culture that values math. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 9. | The harder you work at something, the better you will become. | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 10. | If you want to be kind and you’re not, you can change. | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 11. | Some people are inherently good and kind, and some are not — it’s not often that people change. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 12. | I appreciate when my boss gives me feedback about my performance. | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 13. | I feel defensive or angered when I receive feedback about my performance. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 14. | All human beings without cognitive limitations are capable of the same amount of learning. | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 15. | You can learn new things, but you cannot really change your level of intelligence. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 16. | You can attempt to do things differently, but the important parts of who you are will largely remain the same. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 17. | All human beings are basically good, but sometimes they make terrible decisions. | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 18. | An important reason why I enjoy taking on new coursework is because I like to learn new things. | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 19. | Those people identified as gifted or talented do not need to try hard. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 20. | People should only seek out and participate in hobbies for which they have already demonstrated a talent. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Total | |||||

| Grand Total | |||||

Scoring Key

| Strong Growth Mindset | 45 – 60 points |

| Growth Mindset with Some Fixed Mindset Tendencies | 34 – 44 points |

| Fixed Mindset with Some Growth Mindset Tendencies | 21 – 33 points |

| Strong Fixed Mindset | 0 – 20 points |

I have a fixed mindset. Now What?

The key to changing your mindset lies first and foremost with being self-aware. In order to manipulate your mindset, you must be able to identify situations which commonly trigger your fixed mindset, so that you can be aware of when you’re falling into similar patterns of statements or beliefs.

The following are four key guidelines which can be used to begin retraining your brain toward a growth mindset (Dweck, 2017).

- Learn to hear your fixed mindset voice. When faced with a new challenge, this “voice” might whisper, “Are you sure you can do it?” “What if you fail?” When encountering a setback, this voice may say, “If only you had a natural talent,” or “It looks as if it did not pay for you take the risk.” In the face of feedback from a colleague, the fixed mindset voice says, “This is not your fault,” or “Who do they think they are to criticize me”?

- Recognize that you have a choice. When the voice of doubt begins to creep in, turn that frown upside down and take the challenges, criticism, and missteps as a sign for self-improvement. Respond by deciding to challenge yourself through new learning opportunities, change your strategies, and strive to develop new methodologies or tactics to confront perceived shortcomings.

- Respond to the “inner voice” with a growth mindset voice. In essence, change the dialogue, much like the following.

- The fixed mindset voice says, “You can’t do this.” The growth mindset voice retorts, “I’m not sure I can do it just yet, but I think that with time and effort, I can continue to improve and learn.

- The fixed mindset voice says, “If you fail, your colleagues, students, and principal will always think of you as a failure.” The growth mindset voice replies, “Most successful people encountered their own failures on the pathway to success. I can set a great example for my students by being transparent about my mistakes and sharing what I plan to do the next time so that I can avoid similar errors.”

- The fixed mindset says, “It’s not your fault. The ________ (student, colleague, friend, parent, administrator, stakeholder) contributed to the setback.” The growth mindset voice takes responsibility and responds, “If I do not accept my role, then I won’t be able to correct or prevent the same mistake from happening in the future.”

- Take growth mindset action. Once you have responded to the fixed mindset voice inside you, combat it with specific and measurable actions. An action plan might include embarking on a new challenge, persisting through an old challenge once abandoned, or looking for ways to improve your craft through professional development, professional text, or positive mentorship relationships.

Some people even find it therapeutic and helpful to journal their fixed mindset thoughts as they enter their minds so that they can be addressed using a growth mindset voice. By recording these thoughts, a pattern begins to emerge whereby one is able to glean what sparked the fixed mindset in the first place. Be sure to review all of the dialogues so that they become commonplace in your mind.

After you have challenged the fixed mindset voice with growth mindset practice, it can also be helpful to ask yourself the right questions (Park, 2016). The following is a sampling of questions which can be used for reflection purposes as you work toward determining what your next steps will be. Ultimately, it is questions such as these that serve to assist you as you plan the next steps in your growth mindset action plan. They also make for great “starters” if you choose to journal the fixed vs. growth mindset dialogue as mentioned previously.

- What can I learn from this?

- What steps can I take to help me succeed?

- Do I recognize the outcome or goal I’m after?

- What information can I gather? And from where?

- Where can I get constructive feedback?

- How will I follow through on my plan?

- What did I learn from this experience (positive or negative)?

- What mistake(s) did I make that taught me something?

- Is my current learning strategy working? If not, how can I change it?

- What did I try hard at today?

- What habits must I develop in order to continue the gains I’ve achieved?

It’s a Process

In order to guide ourselves toward the consistent adoption of a deeper and well-developed growth mindset that illuminates our classroom practices, we must acknowledge the existence of the fixed mindset. We must realize we are all a mixture of fixed and growth mindset habits and tendencies and in order to foster the development of a growth mindset, we must honor and combat our fixed mindset thoughts and actions (Dweck, 2017). The background information and understanding that was gleaned from this article can be used to lay a solid foundation for the successful commitment to beginning or continuing the work of Dweck and her colleagues. Interested in hearing about growth mindset directly from guru Carol Dweck? Watch her TED talk to take a deeper dive into growth mindset theory.

To learn more about how to instill a growth mindset in students, visit the Professional Development Institute (PDI) website or go directly to our Instilling a Growth Mindset in Students course. The Professional Development Institute has been offering quality online professional development courses to K-12 educators for over 27 years and provided training to over 345,000 teachers across the globe. We specialize in offering quality, affordable university-approved online courses that focus on the most relevant topics in education while providing practical strategies that can be implemented in the classroom immediately. All PDI courses are at the graduate-level, instructor-led, and are conducted entirely online. University credit is available through University of California Division of Extended Studies. PDI offers an extensive catalog of online courses for teachers on topics that are the most critical in today’s classrooms.

References:

Bolton, J. (2015). “Intelligence as a Malleable Construct.” Retrieved 09 May 2019 from https://akamaihawaii.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Malleable-Intelligence-Combo.pdf

Dweck, C.S. (2015). “Carol Dweck Revisits Growth Mindset.” Retrieved 02 May 2019 from https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2015/09/23/carol-dweck-revisits-the-growth-mindset.html?qs=carol+dweck

Dweck, C.S. (2017) “The Journey to Children’s Mindsets.” In Child Development Perspectives, 11(2), 151-155.

Haimovitz, K. (2016). “Parents’ View of Failure Predict Children’s Fixed and Growth Mind-Sets.” In Psychological Science, 27(6), 859-69.

Horn, I. S., Kane, B. D., & Wilson, J. (2015). “Making sense of student performance data: Data use logics and mathematics teachers’ learning opportunities.” In American Educational Research Journal, 52(2), 208–242.

Lynch, J. (2018). “The Perils of a Good Research Story.” Retrieved 18 June 2019 from https://medium.com/@quixotic_scholar/growth-mindset-the-perils-of-a-good-research-story-d6ce32a447d2

Park, D. (2016). “Young children’s motivational frameworks and math achievement: Relation to teacher-reported instructional practices, but not teacher theory of intelligence.” In Journal of Educational Psychology, 22(1), 315-17.

Rae-Dupree, J. (2008). “If You’re Open to Growth, You Tend to Grow.” Retrieved 06 June 2019 from https://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/06/business/06unbox.html?mtrref=undefined&gwh=457BF2A4328B505685D35689CE36C6B1&gwt=pay&assetType=REGIWALL

Categories: growth mindset, social and emotional learning

View PDI's Catalog of Courses

Check out a list of all PDI graduate-level online courses or sort by grade level or subject area.

Register Now!

Quick access to register for PDI's online courses using our secure system.

Learn More about PDI

Find out how to reach PDI and get answers to any questions you may have.